UIC joins worldwide effort to transcribe Frederick Douglass’ papers for future researchers

x

When University of Illinois Chicago student Ve’Linda Kimble joined the Douglass Day 2024 Transcribe-A-Thon on Feb. 14, she was in awe as she read the words Frederick Douglass put to paper in the 19th century.

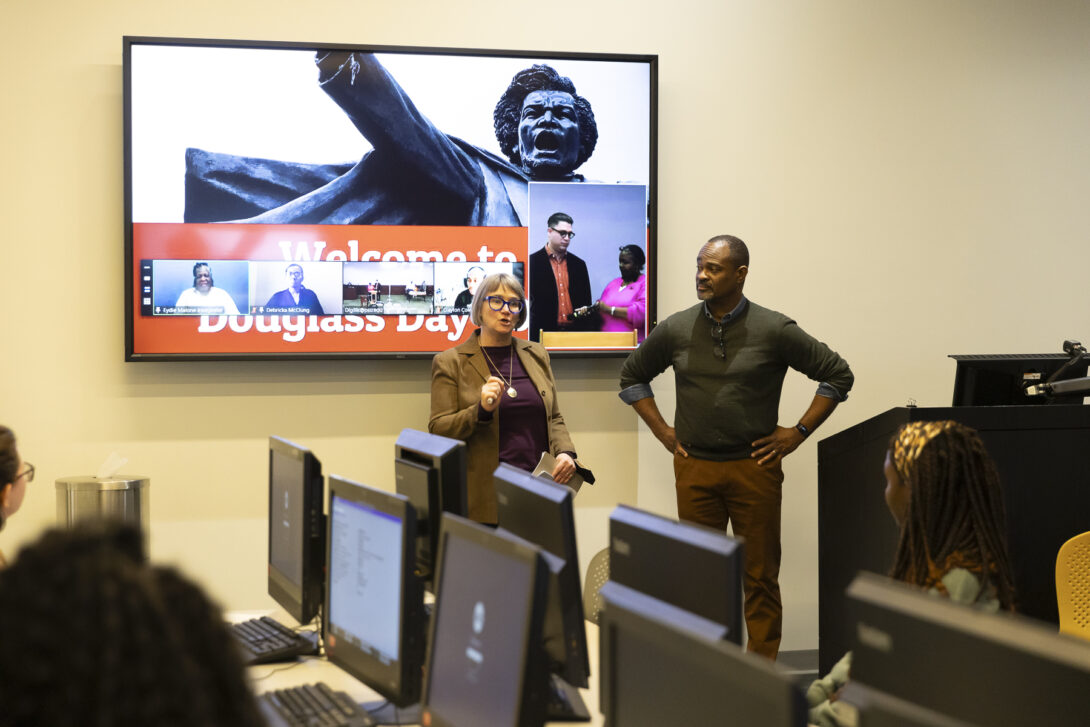

Kimble, a sociology student, was participating in a unique event at the Richard J. Daley Library: To mark the Feb. 14 birthday of the social reformer, abolitionist, writer and statesman, UIC students and faculty joined thousands of others around the world in a day of transcribing Douglass’ handwritten papers held by the Library of Congress.

x

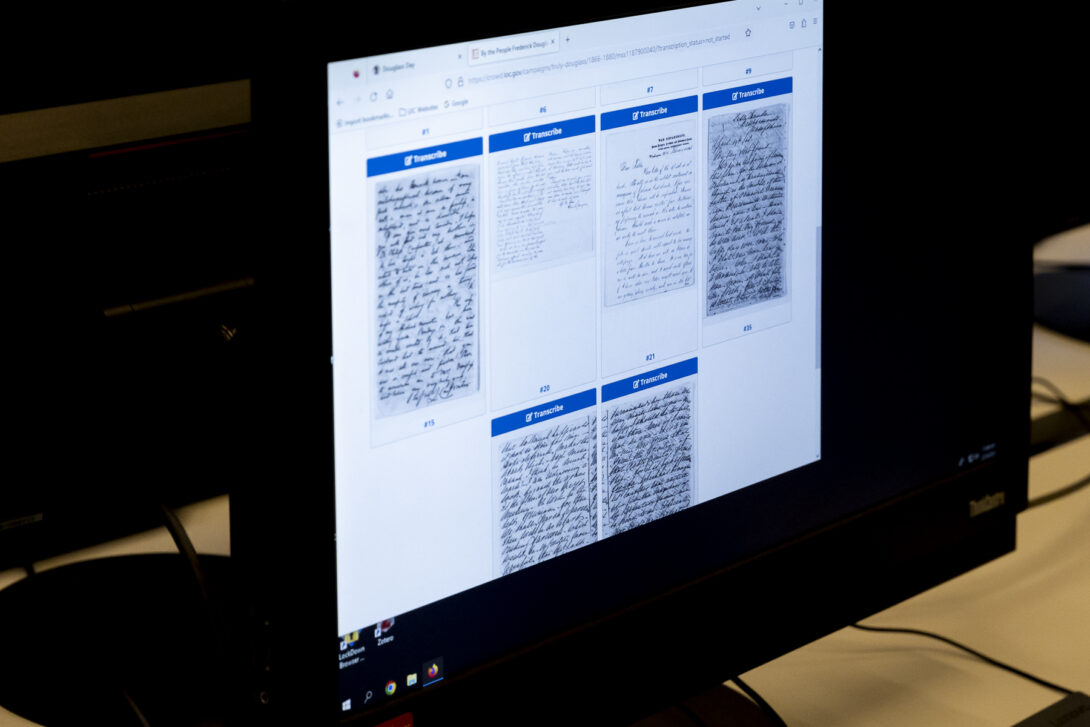

Douglass wrote in a flowery 19th-century cursive, setting up a challenge for the participants to decipher his handwriting and turn it into digital text. The worldwide effort aimed to make Douglass’ historic papers more accessible for researchers and students for years to come.

The UIC Library and the departments of Black studies, sociology and history sponsored the UIC transcription event, which also celebrated Black History Month. Douglass’ birthday is one reason Black History Month is held in February.

Kimble said she wanted to participate because she felt it was essential to share Douglass’ words and make them accessible to others.

“I’m very, very overwhelmed,” Kimble said. “I want to know exactly, by the expression of these letters, what his thoughts were as he began to take the time to spill them out with ink on paper. I want to know where he was in thought.”

x

Adjo Tetedje, an applied psychology student, said that as a recent immigrant from Ghana, she decided to participate in the Transcribe-A-Thon to interact with other Black students at UIC and learn about Douglass. Before the event at the library, she was unaware of Douglass’ role in U.S. history. But as she transcribed his words, she grew impressed with his output and intellect.

“I find it interesting. He’s trying to deliver a message to someone,” said Tetedje, as she tried to read Douglass’ ornate handwriting.

Rasheedah Na’Allah, a sociology major, said as a Black student, she appreciates that her teachers focus on Black history and topics every February. Though she has learned about Douglass and his role in American history, she’s never had a chance to see his handwritten papers.

“This is my first time actually getting to see his work and see how much work he had; there’s so much of it,” Na’Allah said. “It’s really inspiring to look at, and it’s really cool to see that he was someone just like us who liked to write about his feelings.”

x

Joseph Jewell, professor and head of Black studies, said the event is part of a mission to make archival materials available to the public. When students, faculty and visitors gathered at the library to participate, they logged in to the Douglass Day website, where they could access the scanned original documents. Briana Hanny, the Black Studies program director, helped organize the event.

“It is in the original late 19th- to early-20th-century script,” Jewell said. “Participants get a great opportunity to see what archival research looks like by participating hands-on.”

Douglass’ influence in the abolitionist movement, his push for civil rights for Black people and his advocacy of education for everyone are still significant today, Jewell said.

“Frederick Douglass was a huge advocate of education as not only a means of self-improvement but empowerment. He believed that education was necessary for a democratic society to function and the importance of truth,” Jewell said.

Amy Bailey, associate professor of sociology, said more than 30 people registered to participate at UIC in the Transcribe-A-Thon and as many as 8,000 participated worldwide.

Bailey said transcribing Douglass’ writing will allow his words to inform people as Black history education is facing hurdles in many areas across the U.S.

x

“When we see politically motivated efforts happening around the country these days to roll back access to a full knowledge of our nation’s history, I think it’s really important that we push back against that,” Bailey said.

Kellee Warren, assistant professor and special collections librarian, said the transcription event was a way to keep history alive at a time when many schools have stopped teaching cursive reading and writing to young students. This has implications for deciphering handwritten historical documents, she said.

But the transcriptions from the Feb. 14 event will allow others to learn from the correspondence Douglass shared with his contemporaries.

“I want people to recognize that they are historical actors,” Warren said, “that they have the power to create history, to interpret history and to transcribe history.”